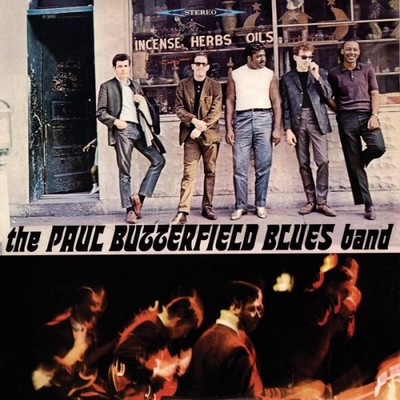

Sam Lay runs through Chicago blues history like a sinuous beat underlying a Muddy Waters lick. Make that a double-shuffle beat – the signature sound Lay developed as a drummer for Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, Paul Butterfield, and other Chicago luminaries. When Dylan went electric at Newport in ’65, Sam Lay was behind the kit, and his prodigious rhythms on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album

Sam Lay runs through Chicago blues history like a sinuous beat underlying a Muddy Waters lick. Make that a double-shuffle beat – the signature sound Lay developed as a drummer for Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, Paul Butterfield, and other Chicago luminaries. When Dylan went electric at Newport in ’65, Sam Lay was behind the kit, and his prodigious rhythms on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album

Still going strong at 80, Lay gets a deserved star turn in John Anderson’s film, which premiered, fittingly, at the Chicago International Movies & Music Festival in April, just after Lay was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Shot through with performances by Lay with his own quartet and the Siegel-Schwall Blues Band, the doc captures his singular sartorial style (he’s partial to capes, crowns, and jeweled canes) and storied musical history with a mix of rollicking recollections and a trove of vintage, intimate footage Lay shot of fellow blues greats at work and play in Chicago clubs.

The movie cements Anderson’s place as a cinematic historian of Chicago blues, coming on the heels of Born in Chicago, his 2013 documentary on the white kids like Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, Corky Siegel, Nick Gravenites, and Barry Goldberg who immersed themselves in the city’s black music scene and carried the blues torch to the Woodstock generation. A music doc veteran known for his work with Brian Wilson, Anderson is in the late stages of a PledgeMusic campaign to raise money for Born in Chicago’s music and video licensing, prefatory to a cinema and digital release. Perks include copies of the forthcoming Born in Chicago soundtrack signed by Sam Lay and other contributing artists; the campaign runs until September 16.

On the 25th, Anderson and Lay will be in the house for a screening of Sam Lay in Bluesland at the University of Illinois-Springfield, making the timing even more propitious to post an interview with the filmmaker by Chicago-based writer, musician, and friend of MFW Steve Karras, whose other claim to fame is having attended the same synagogue as Mike Bloomfield.

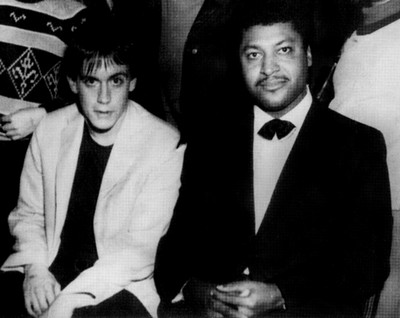

John Anderson and Sam Lay after a May 2014 gig filmed for rmusic documentary Sam Lay in Bluesland. Photo/Bobby Lay

Steve Karras: Are you a Chicagoan originally?

John Anderson: I came here to go to college in the early ’70s and stayed, basically. So I’ve been here for most of my adult life.

Was music at the forefront of your interest?

It was always music and filmmaking. It started out in the film field, in the editorial side. I was an editor for many years at a few companies around town, doing every sort of project, including music videos. When music videos came to the fore around the time of MTV and the early ’80s, my band, the Cleaning Ladys, made a bunch of early music videos.

Were you seeking [blues] guys out to work with, to document?

The original story, how this handful of white kids had done what they did as far as finding and disseminating the blues – that was when I was introduced to Timm Martin, who owns the record company Out the Box that Chicago Blues Reunion is on, which is Barry and Corky and Harvey [Mandell] and Nick. I met him in 2004, and then in 2008 he gave me the green light to make that film, Born in Chicago. That is what got me thoroughly immersed in the scene, and now Sam is a subset of that.

These white kids, I always thought they did as much justice [to the blues] if not more so than the people who came later, like the Stevie Rays. Bloomfield is just one the most overlooked guitar players. And they did their time – they played in the same clubs on the West Side and South Side as the people they idolized.

To me the thing is, it’s one thing to go down to the clubs and learn at the feet of the masters. It’s another thing to go on and master your own instrument and your own life out of that, to carve a life for yourself in the blues. It was no easier in the ’50s and ’60s than it is now. Each of these guys, when you think about it – Nick, Barry, Steve Miller, all of them – they can still play great. That’s what earned them the respect of the masters, and to hear them play today, in their late 60s and 70s, it tells you the quality of their playing is what made it happen. They all just absorbed the soul of the blues and formed, each of them, their own iconoclastic instrumental and vocal style.

With Sam Lay, I’d heard of him like anybody else, knowing he was in the Butterfield Blues Band, but I’d never heard him interviewed. Here’s a guy that was probably one of the more authentic blues guys in the band, who’d played with some of the – didn’t he play with Howlin’ Wolf or with Muddy Waters before he ever met Butterfield?

With Sam Lay, I’d heard of him like anybody else, knowing he was in the Butterfield Blues Band, but I’d never heard him interviewed. Here’s a guy that was probably one of the more authentic blues guys in the band, who’d played with some of the – didn’t he play with Howlin’ Wolf or with Muddy Waters before he ever met Butterfield?

And Little Walter, yeah. He’s like a Zelig of the blues. It’s remarkable. At 24 he was playing in Little Walter’s band. Not only playing in Little Walter’s band, he was living with him. The thing about Sam is he’s a peacemaker, everybody loves him. Before Little Walter even knew that he was a drummer, he met Little Walter and Little Walter took him in. Sam and his wife didn’t really have a good place to stay other than [with] her relatives. They took him in, he played with them, and [then] Sam goes with Wolf. Wolf was a life friend, and Wolf’s wife, Lillie, until she passed was close friends with Sam and his wife, and they’re still close with Wolf’s daughter. It’s a beautiful love story underneath it, of real human beings. These were real guys who were fighting for a living. They still managed to have time to be really good to each other.

At one point did you decide you wanted to make a film specifically about him? What made you take the plunge?

I took a friend of mine, Michael Prussian, to a Chicago Blues Reunion rehearsal. I think it might have been in June of 2013, as they were rehearsing for the gig they had the next night at [Chicago venue] The Vic that they sold out, where they showed the film and brought out the stars of the film – it was this big event. So they’re all there at this rehearsal place on the West Side called the Chocolate Factory, and I knew Michael was a blues fan. He just observed the proceedings, and Sam was kind of showing off for me between takes. He put on his guitar and was holding court, as he does, just telling his stories. Michael witnessed this, and afterward he said, “You know, we should make a film about Sam Lay.” He went on to become the executive producer and make the whole thing possible. Just that kinetic moment that he had, as we all feel when we’re around Sam, in that little rehearsal room.

And you got to be the beneficiary of that on the creative side.

Yeah. Talk about lucky, and right time and right place.

I remember reading in a punk rock book – it was called Please Kill Me

The credit for that goes to Starr Sutherland, our producer. He was the first person that became aware of that. After he became aware of that I thought I might have read something about it in Please Kill Me and I looked it up. Starr had the connection to Iggy, he knows his manager. Another one of those hundreds of fortuitous things that seemed to happen for this film – he called him up and Iggy said, “Are you kidding? When can you get here?”

Was everyone always receptive to the idea of being part of the film?

If it has to do with helping Sam or supporting Sam, everyone gives an immediate yes. He’s someone that everyone loves, everyone knows is really talented, and everyone knows the story of whom should get out there. Pardon my grammar, but you know what I’m trying to say. They’re as amazed as I am that this story hasn’t been told before. As we were about the Born in Chicago story.

Did you see Bob Sarles’s film on Mike Bloomfield [Sweet Blues, a one-hour doc included in the 2014 Bloomfield box set From His Head to His Heart to His Hands]?

Yeah, I thought it was good. Too short, you know?

I take pride in the fact that my mom went to his bar mitzvah. And my uncle, he tells me a couple of Bloomfield stories. As a kid he used to go see the Kingston Trio at Ravinia [a venerable open-air Chicago music festival]. He’s like 13, and there’s a couple older guys behind him, and he hears one of ‘em say, “Aw, these guys ain’t shit.” And it was Mike Bloomfield.

[Laughs] Well, none of these guys were shrinking violets. Every one of them is bigger than life. From Nick Gravenites to Harvey Mandell, to of course Sam, and Steve Miller, all the people that we’ve been through, Eric Burdon. It has something to do with having the blues. It’s somehow related to this strength. It took people who were sure of themselves to stand up in the world that they had to [stand up in]. That hasn’t changed over the years. Nor has their playing. They can all just play the shit out of their instruments.